Capital Region II Individual Highlight: Photographer Bernie Kolenberg

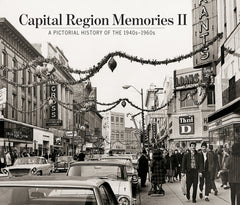

The upcoming pictorial history book, Capital Region Memories II: The 1940s-1960s, features photos from the Times Union photographic archives taken by daring Times Union photographer Bernie Kolenberg, the first American journalist killed in action in the Vietnam conflict.

Tom Wilkinson and Bernie Kolenberg hiking on February 17, 1963

We can learn more about his life, and how he came to be in Vietnam, from an October 2, 2015 Times Union article by Paul Grondahl:

Bernie Kolenberg, a tousle-haired Times Union photographer, who raced breathlessly to crashes, fires and explosions clutching two Leica M3 cameras, trademark bow tie slightly askew, died 50 years ago this week.

The 38-year-old Troy native was killed on Oct. 2, 1965 in Vietnam, the first American journalist killed in action covering the war.

He had taken a second leave of absence from the Times Union and was on assignment for one week with the Associated Press when the U.S. Air Force Skyhawk he was riding in collided with another fighter-bomber over the Bing Dinh province.

In the spring of 1965, he had spent five weeks in Vietnam as a freelance photographer and returned to his wife, Mary, 8-year-old son, Kevin, in Wynantskill and his job at the paper.

But he was a photojournalist at heart and always wanted to be where the action was.

"He knew Vietnam was the big story and he was always looking for the big story," said Pulitzer Prize-winning author William Kennedy, a former Times Union reporter who frequently covered assignments with Kolenberg. "He did whatever it took to get a great picture."

The late Times Union columnist John Maguire said Kolenberg "was slugged, shot at and chased in the line of duty." He described him as "a Page One Man" — a photographer whose images were so powerful they almost always were displayed on the front page.

Sid Brown, a photographer for the Daily Gazette in Schenectady, was a competitor who forged a friendship with Kolenberg over years of shooting accidents, crime scenes and sundry assignments.

"He was a great photographer and I always admired his work," said Brown, 88, of Schenectady, who retired in 1992 after 44 years as a Gazette photographer.

The last time Brown saw Kolenberg — the two went camping in the Adirondacks with their families and traveled to New York City and Washington, D.C. together on assignment — was when they covered the Capital District Scottish Games at the Altamont Fairground in September, 1965.

He told Brown he was going back to Vietnam. They discussed the danger of covering combat and Brown tried to talk Kolenberg out of returning to the war zone. It was no use.

"I just have to go," Kolenberg said.

Kolenberg died less than a month later "in duty he loved," according to a story by the Pulitzer Prize-winning war correspondent Peter Arnett. Kolenberg showed up at the Saigon bureau of the AP, dropped his cameras and gear on a desk and declared, "It's great to be back." Arnett said. He recalled that Kolenberg worked with "infectious good humor."

Workers at the Atlantic Cement Company facility near Ravena, 1961.

Bernard J. Kolenberg was born in Troy, attended Hillside School and concluded his formal education in the eighth grade. He got a job as a copy boy at the Times Union in 1946. He was energetic, ambitious and would not be denied a job as a photographer. Editors started giving the kid with the loopy grin and relentless drive occasional assignments. Soon, his talent shone for all to see.

"He had a terrific eye," recalled Kennedy, 87, of Averill Park, who wrote a moving tribute, "An Epitaph for Bernie," that was published in the Times Union on Oct. 4, 1965.

In that piece, he called Kolenberg "a folk hero among journalists, a myth maker" who left a trove of stories about his legendary exploits.

The Times Union city editor at the time, Barney Fowler, who later became a popular columnist, described Kolenberg as "at times brash, a highly complex individual, and one of great sensitivity, with the mark of the true artist."

As his boss, he considered Kolenberg "a combination (of) problem and delight."

Fowler fielded calls from angry representatives of Niagara Mohawk (today's National Grid), who ordered Kolenberg to stay off their power poles, which he often scaled — risking electrocution — to get a better vantage point for a shot of a marooned cat or some type of frightened, stranded critter.

That's what a Page One Man did.

Kennedy recalled a routine assignment of a radio tower construction site that Kolenberg turned into an award-winning image. He talked workers into hoisting him with a derrick more than 100 feet into the air so he could take a high-altitude, wide-angle image.

"He got way up there, he got his shot and then he was frozen with fear, clinging to the tower," Kennedy said, beginning to roll with laughter. "Bernie couldn't move. Finally, some firefighters got a rope on his leg and enticed him to start moving down."

Another time, Kolenberg convinced the mayor of Troy to dive off a diving board into a pond at the old Albany Country Club for a photo.

"Bernie had a way with people that was intuitive, absolutely fearless, with no social reservations about intruding on someone," Kennedy said.

He did it with a goofy joke, a throaty laugh and often a malaprop.

"Bernie was a singular character, absolutely beloved," said Kennedy. The newspaper's staff started collecting what became known as "Bernie-isms."

Joffrey Hill, 13 months, at a National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) march on the Capitol, February 28, 1961

When they allowed themselves to daydream about making it to the big time of journalism, Kolenberg asked Kennedy, "When you gonna win the Pulitzer Surprise?"

Kennedy described the time Kolenberg invited the reporter to join him on an in-depth photojournalism series he was working on about alcoholics who lived on the streets around the Gut in the city's South End. That was an era before the term homeless was coined.

Kolenberg had befriended a grizzled street person named Buddy and spent hours hanging out with him, taking pictures of Buddy and a woman named Mary in a hobo encampment and a flop house.

Kennedy joined the photographer and turned it into a series of feature articles. "But then the cops came and rounded them up and threw them in jail because the stories and photos made the city look bad," Kennedy said.

The two journalists followed up and spent more time on the streets with Buddy and Mary after they were released from jail. Those two street people became the inspiration for Kennedy's Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, "Ironweed," about Depression-era bums in Albany. The book's two main characters are Francis Phelan and Helen, played by Jack Nicholson and Meryl Streep in the film version.

"I have Bernie to thank for bringing me into that story," Kennedy said.

Brown called Kolenberg an innovator, one of the first among the Capital Region's news photographers to switch in the 1950s from the bulky, medium-format Speed Graphic camera to the sleek, lightweight 35mm Leica M3.

"The older guys looked down their noses at Bernie at first, but they had to admit he took great pictures," Brown said.

Bernard Kolenberg’s casket arriving home to Albany.

Kolenberg was honored posthumously by the National Press Club in Washington D.C. and at a 1986 ceremony at Arlington National Cemetery for more than 200 American war correspondents killed in past wars.

Shortly before he was killed in 1965, Kolenberg accepted the state Associated Press Association prize for that year's best feature photograph. An annual AP photo award is named for Kolenberg. The State Museum mounted an exhibit of his work in 1965, "The Faces of Vietnam." His widow donated more than 300 Kolenberg photographs to the Tri County Council of Vietnam War Veterans.

Kolenberg is included in a Vietnam War memorial in Troy.

These and hundreds of other gorgeous historical photos can be found in Capital Region Memories II. Click the link below to purchase!

CapitalRegion2.PictorialBook.com

$44.95